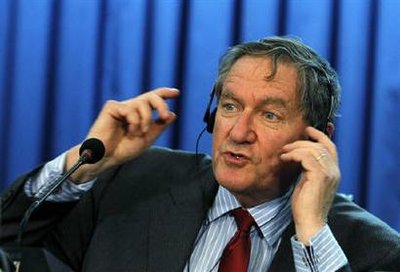

Richard Holbrooke, a brilliant and feisty U.S. diplomat who wrote part of the Pentagon Papers, was the architect of the 1995 Bosnia peace plan and served as President Barack Obama’s special envoy to Pakistan and Afghanistan, died Monday, the State Department said. He was 69.

Richard Holbrooke, a brilliant and feisty U.S. diplomat who wrote part of the Pentagon Papers, was the architect of the 1995 Bosnia peace plan and served as President Barack Obama’s special envoy to Pakistan and Afghanistan, died Monday, the State Department said. He was 69.

Calling Holbrooke “a true giant of American foreign policy,” Obama paid homage to the veteran diplomat as “a truly unique figure who will be remembered for his tireless diplomacy, love of country, and pursuit of peace.” Holbrooke deserves credit for much of the progress in Afghanistan and Pakistan, the president said.

Holbrooke, whose forceful style earned him nicknames such as “The Bulldozer” and “Raging Bull,” was admitted to the hospital on Friday after becoming ill at the State Department. The former U.S. ambassador to the U.N. had surgery Saturday to repair a tear in his aorta, the body’s principal artery.

Secretary of State Hillary Clinton called Holbrooke one of America’s “fiercest champions and most dedicated public servants.”

“Richard Holbrooke served the country he loved for nearly half a century, representing the United States in far-flung war zones and high-level peace talks, always with distinctive brilliance and unmatched determination,” Clinton said.

Holbrooke served under every Democratic president from John F. Kennedy to Obama in a lengthy career that began with a foreign service posting in Vietnam in 1962 after graduating from Brown University, and included time as a member of the U.S. delegation to the Paris Peace Talks on Vietnam.

On Capitol Hill, Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman John Kerry, D-Mass., called the loss of Holbrooke “almost incomprehensible,” adding that his “tough-as-nails, never-quit diplomacy” saved tens of thousands of lives. Republican Rep. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen of Florida, who will chair the House Foreign Affairs Committee next year, called Holbrooke “a dynamic force in American diplomacy” whose “stellar service is deeply appreciated and held in the highest esteem.”

Holbrooke’s sizable ego, tenacity and willingness to push hard for diplomatic results won him both admiration and animosity.

“If Richard calls you and asks you for something, just say yes,” former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger once said. “If you say no, you’ll eventually get to yes, but the journey will be very painful.”

He learned to become extremely informed about whatever country he was in, push for an exit strategy and look for ways to get those who live in a country to take increasing responsibility for their own security.

“He’s a bulldog for the globe,” Tim Wirth, president of the United Nations Foundation, once said.

The bearish Holbrooke said he has no qualms about “negotiating with people who do immoral things.”

“If you can prevent the deaths of people still alive, you’re not doing a disservice to those already killed by trying to do so,” he said in 1999.

Born in New York City on April 24, 1941, Richard Charles Albert Holbrooke had an interest in public service from his early years. He was good friends in high school with a son of Dean Rusk and he grew close to the family of the man who would become a secretary of state for presidents Kennedy and Johnson.

Holbrooke was a young provincial representative for the U.S. Agency for International Development in South Vietnam and then an aide to two U.S. ambassadors in Saigon. At the Johnson White House, he wrote one volume of the Pentagon Papers, an internal government study of U.S. involvement in Vietnam that was completed in 1967.

The study, leaked in 1971 by a former Defense Department aide, had many damaging revelations, including a memo that stated the reason for fighting in Vietnam was based far more on preserving U.S. prestige than preventing communism or helping the Vietnamese.

After stints in and out of government — including as Peace Corps director in Morocco, editing positions at Foreign Policy and Newsweek magazines and adviser to Jimmy Carter’s presidential campaign — Holbrooke became assistant secretary of state for Asian affairs from 1977-81. He then shifted back to private life — and the financial world, at Lehman Brothers.

A lifelong Democrat, he returned to public service when Bill Clinton took the White House in 1993. Holbrooke was U.S. ambassador to Germany from 1993 to 1994 and then assistant secretary of state for European affairs.

One of his signature achievements was brokering the Dayton Peace Accords that ended the war in Bosnia. He detailed the experience of negotiating the deal at an Air Force base near the Ohio city in his 1998 memoir, “To End a War.”

James Dobbins, former U.S. envoy to Afghanistan who worked closely with Holbrooke early in their careers, called him a brilliant diplomat and said his success at the Dayton peace talks “was the turning point in the Clinton administration’s foreign policy.”

Holbrooke’s efforts surrounding Dayton would later lead to controversy when wartime Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic told a war crimes tribunal in 2009 that Holbrooke had promised him immunity in return for leaving politics. Holbrooke denied the claim.

Holbrooke left the State Department in 1996 to take a Wall Street job with Credit Suisse First Boston, but was never far from the international diplomatic fray, serving as a private citizen as a special envoy to Cyprus and then the Balkans.

In 1998, he negotiated an agreement with Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic to withdraw Yugoslav forces from Kosovo where they were accused of conducting an ethnic cleansing campaign and allow international observers into the province.

“I make no apologies for negotiating with Milosevic and even worse people, provided one doesn’t lose one’s point of view,” he said later.

When the deal fell apart, Holbrooke went to Belgrade to deliver the final ultimatum to Milosevic to leave Kosovo or face NATO airstrikes, which ultimately rained down on the capital.

“This isn’t fun,” he said of his Kosovo experience. “This isn’t bridge or tennis. This is tough slogging.”

Holbrooke returned to public service in 1999, when he became U.S. ambassador to the United Nations after a lengthy confirmation battle, stalled at first by ethics investigations into his business dealings and then unrelated Republican objections.

At the U.N., Holbrooke tried to broker peace in wartorn African nations. He led efforts to help refugees and fight AIDS in Africa. He also confronted U.N. anger over unpaid U.S. dues to the world body and persuaded 188 countries to overhaul the United Nations’ financing and reduce U.S. payments.

“What’s the point of being in the government if you don’t try to make things better, which means trying to change things,” Holbrooke told The Associated Press in a 2001 interview, reflecting on his time at the United Nations.

Holbrooke, with his long-standing ties to Bill Clinton and Hillary Rodham Clinton, was a strong supporter of her 2008 bid for the White House. He had been considered a favorite to become secretary of state if she had won. When she dropped out, he began reaching out to the campaign of Obama.

“Richard Holbrooke saved lives, secured peace and restored hope for countless people around the world,” Bill Clinton said in a statement late Monday.

Reflecting on his role as Obama’s special envoy, Holbrooke wrote in The Washington Post in March 2008 that “the conflict in Afghanistan will be far more costly and much, much longer than Americans realize. This war, already in its seventh year, will eventually become the longest in American history, surpassing even Vietnam.”

Holbrooke’s relationship with Afghan President Hamid Karzai was strained after their heated meeting in 2009 over the fraud-tainted Afghan presidential election. Karzai brushed it off, saying he had “no problem at all with Mr. Holbrooke.” But the U.S. military commanders in Afghanistan, not Holbrooke, were the ones who ended up developed the closest relations with the mercurial Afghan leader. The State Department said Sunday that Karzai and Pakistani President Asif Ali Zardari were among those calling to wish Holbrooke well.

Holbrooke rejected direct comparisons between Afghanistan and Vietnam, but acknowledged similarities and repeatedly pressed the administration to do more to win the hearts and minds of both the Afghan and Pakistani people.

He was fully engaged in that effort until his unexpected death.

A torn aorta — the condition that cost Holbrooke’s life — is a rip in the inner wall of the body’s largest artery. The result is serious internal bleeding, a loss of normal blood flow and possible complications in organs affected by the resulting lack of blood, according to medical experts. Without surgery it generally leads to rapid death.

“True to form, Richard was a fighter to the end,” said Clinton. “His doctors marveled at his strength and his willpower, but to his friends, that was just Richard being Richard.”

Holbrooke is survived by his wife, author Kati Marton, and two sons from an earlier marriage, David Holbrooke and Anthony Holbrooke.