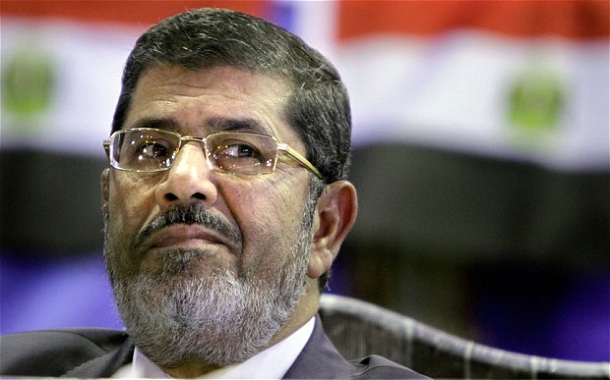

Egypt Unrest:Egypt was the first sign of the end of Political Islam / Breaking News

Political islam favorite of the last 10 years for the United States, President Obama three weeks ago said ” We are not work with islamist anymore ” Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, and was the first example of Obama’s words.

It was the moment that many had been expecting for two days, ever since the military had given Morsi a 48-hour ultimatum to change course. The deadline had been issued in response to growing mass protests against the Islamist president. And on Wednesday night, the military moved in to depose Morsi, setting up a temporary civilian government and promising that new elections would be held soon. The chief justice of the country’s highest court is to be sworn in as interim president on Thursday.

On Wednesday morning, however, it looked as though a clash was imminent. The two enemy political camps had assembled in Cairo, separated by about one kilometer (about two thirds of a mile). On Tahrir Square in the heart of the metropolis, a huge group of people was in a celebratory mood, anticipating a victory over the hated President Morsi. With the military’s ultimatum soon to expire, the opposition knew that victory would be theirs.

Those gathered in Nasr City, though, were not yet prepared to accept the approaching defeat of the Muslim Brotherhood. Just minutes before the ultimatum was to expire on Wednesday afternoon, hundreds collected in front of the Raba’a al-Adaweya Mosque, preparing to go to battle for their president. Armed with clubs, they listened to their final instructions with stony-faced seriousness. The word “shahid,” or martyr, was on everyone’s lips.

They did their best to exude a kind of forced optimism — in full knowledge that the day could end in disaster. Still, the Muslim Brotherhood is not a group to be underestimated. Forbidden under the rule of Hosni Mubarak and before, the Islamists spent years in the underground, many of them locked away in prisons and tortured. They have 85 years experience in resisting state power.

The generals, though, first let the deadline pass without a whisper. After an hour or two, the gathered Islamists also seemed to relax slightly, setting aside their clubs and drinking tea in the shade. The owner of a flower shop took out his old television and set it up on the sidewalk.

The mood was tense, but not as aggressive as hours earlier. Regardless, an argument over the remote control began to escalate. Why watch the Muslim Brotherhood channel, Egypt 25, a man railed. “We’re just going to see ourselves.” The channel indeed was broadcasting live footage of the demonstration — the Islamists are mercilessly self-centered to the bitter end.

Only those with smartphones knew what was actually going on: Morsi and other leaders of the Brotherhood had been placed under house arrest, and the army was pouring out of their barracks into the streets. Journalists tweeted pictures showing how soldiers had occupied the Nile bridge. “Throw the phone away,” whispered a man fearing the reactions of bystanders.

Egypt Unrest:The Muslim Brotherhood could not use the credit

Suddenly, the army helicopter began circling again and news quickly circulated that the military had joined Morsi’s opponents. Immediately, concern spread. What would happen to them? Many began speaking of possible show trials.

Driving the Muslim Brotherhood back underground, however, seems unlikely now that the Islamists have had a taste of power. Indeed, elsewhere in the country, clashes between the Islamists and the army erupted immediately. At least 14 people were killed, according to a Reuters report on Thursday morning.

Support for the Muslim Brotherhood in the country likewise remains substantial. And two hours after Morsi’s supporters lost their leader, General Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi took to the airwaves to announce how the military planned to proceed.

He said that Morsi had been deposed and placed in military custody, the constitution had been suspended, and the chief justice of the Supreme Constitutional Court will lead the country until further notice. In addition, 38 senior members of the Muslim Brotherhood have been rounded up. The court, Sissi said, is currently working on a new electoral law to prepare for upcoming elections. Sissi did not give a detailed time frame.

What the defense minister did not say is that, with the coup, he had ended an experiment on which more than half of all Egyptians had rested their hopes less than a year ago. And he had no answer to the question that is drowned out by the deafening jubilation in Tahrir Square: Has there ever been a military coup with a happy ending?

Immediately after the broadcast of Sissi’s speech, Egypt’s Islamist television channels were shut off. Egypt 25 remains a black screen. It is a very bad start for what Sissi called an initiative of “national reconciliation.”

Egypt Riot:Status of political Islam in Turkey right now

Turkey against the Islamist Justice and Development Party there. I’ve seen an Iranian election where Iranian voters – who were only allowed to choose between six candidates pre-approved by Iran’s clerical leadership – quickly identified which of the six was the most moderate, Hassan Rowhani, and overwhelmingly voted for him. And I’ve seen the Islamist Ennahda party in Tunisia forced by voters there to compromise with two secular center-left parties in writing a constitution that is broad based and not overly tilted toward Shariah law. And just a year ago in Libya, I saw a coalition led by a Western-educated political scientist beat its Islamist rivals in Libya’s first free and fair election.

Again, it would be premature to say that this era of political Islam is over, but it is definitely time to say that the more moderate, non-Islamist, political center has started to push back on these Islamist parties and that citizens all across this region are feeling both more empowered and impatient.

The fact that this pushback in Egypt involved the overthrow of an elected government by the Egyptian army has to give you pause; it puts a huge burden on that army – and those who encouraged it – to act in a more democratic fashion than those they replaced. But this was a truly unusual situation. Why did it come about and where might Egypt go from here?

Meanwhile, the Obama Administration was largely a spectator to all of this. The Muslim Brotherhood kept Washington at bay by buying it off with the same old currency that Mubarak used: Arrest the worst Jihadi terrorists on America’s most-wanted list and don’t hassle Israel – and the Americans will let you do whatever you want to your own people.

Erdogan, of course, is Recep Tayyip Erdogan , prime minister of Turkey since 2003 as head of the ruling Justice and Development Party, or AKP, which fancies itself the leading edge of a new wave of moderate political Islam. Kotsev writes:

While the Turkish government spent much of the last couple of years branding itself as a paradigm for Egypt and other Arab Spring countries, the reverse is now taking place: Egypt is becoming the nightmare scenario for Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

It’s a nightmare in several senses. For one thing, Turkey has spent vast sums of money and political capital trying to tout itself and Egypt as leaders of the new wave. The victory of the Muslim Brotherhood last year in Egypt, the Arab world’s most popular country, was Erdogan’s chance to show that his brand of democratic Islamism had graduated from test-case to movement. Now, as Wall Street Journal reporter-blogger Joe Parkinson wrote today,

Analysts said that the prospect of the fall of Egypt’s democratically-elected Islamist government, could represent a serious blow to Turkey’s aspirations of regional leadership.

“The developments in Egypt are unfortunate, but along with the situation in Syria, it appears to mark the end of whatever dreams the Turkish government previously had of playing a leading role to a series of friendly Islamist governments in the region,” said Soli Ozel, professor of International Relations at Istanbul’s Kadir Hass University.

And not just dreams of regional leadership. Turkey has been rocked by major street protests of its own for the past five weeks. The violent phase seems to have ended—with a brand-new court victory for the protesters, it’s worth noting, annulling the parkland development project that brought them into the street—the mere fact that the protests could topple his fellow Islamist to the south has to be making Erdogan a tad nervous.

And on top of that, the coup de grace was delivered by the army, the institution that’s been Erdogan’s greatest bane since the beginning. Kotsev:

True, the danger of a military coup in Turkey at the moment is close to zero, if only because Erdogan has locked up an entire army college (some 330 officers) on charges of plotting against him. But the parallels between the two countries run far beyond the superficial. For the record, so too did Egyptian still-President Mohammed Morsi try to purge the army last year, although he only removed a few top generals

Most importantly, both countries are experimenting with moderate political Islam, and the experiments have produced mixed result as far as genuine democracy is concerned.

As for America’s broken dreams, they also began a decade ago, when President Bush decided to adopt the strategy of exporting democracy as the way to tame the Middle East and “defeat the terrorists.” This is where it’s gotten us. Here’s Ratnesar in Bloomberg Businessweek:

Morsi’s removal may well empower forces that are more friendly to the U.S. than the Muslim Brotherhood. It also signals the end of a decade-long U.S. project to bring democracy to the Middle East.

In the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, the administration of George W. Bush initiated a profound shift in U.S. foreign policy. The U.S. would no longer continue to give a blank check to autocratic Arab regimes that deprived their citizens of political liberty. The logic of the Freedom Agenda, as it came to be known, was that democracy would help ease the frustrations of restive Arab populations and stem the appeal of Islamic extremism. That theory was one of Bush’s main justifications for invading Iraq, a decision that ultimately brought to power a government allied with Iran. The Bush Administration also pushed for elections in the Palestinian Authority—which were won by Hamas, an organization committed to Israel’s destruction.

The debacle of the Iraq War was a major factor in Barack Obama’s presidential victory in 2008, and he immediately began to pivot away from the democracy agenda, to the fury of his conservative detractors. He declared his new approach in a 2009 speech in Cairo. Ratnesar:

As the Arab Spring unfolded in 2011, however, Obama more openly embraced democratization. The administration gave tacit support to the revolution in Tunisia, publicly called for Mubarak to step down, and undertook military action to aid the rebellion against Libya’s Muammar Qaddafi.

The result has been, in a word, chaos. Of the countries in the Middle East in which the U.S. has supported regime change since 2003, only Tunisia can be said to be anything resembling a stable, functioning state.

[adrotate banner=”64″]